Learning to train archaeologists

After the two-month excavation in Policastro Bussentino last year, I was keen to improve on the skills I had learned. I had discovered during that excavation that I was actually really interested in taking more of a leadership role, but was not yet sure how much I knew, or yet needed to learn, to do so. A fortunate meeting with my former teacher, Dr. Ben Russell from the University of Edinburgh, alerted me to a dig that would be happening in Aeclanum (modern Mirabella Eclano) for September 2016. The excavation is an ongoing joint-venture with the University of Edinburgh and the Apolline Project(http://www.apollineproject.org/) with co-director, Ferdinando De Simone.

Dr Moodie-Currie, Dr King, and Me (from left) surprisingly clean !

With this in mind, I had been anticipating an exciting few weeks with two of my brilliant friends, both currently undertaking PhDs at the University of Saint Andrews and Edinburgh University. Packing for the trip (both passports in tow!) is one of the best parts…slowly I am getting more and more efficient.

With a few days spent adventuring and relaxing in Rome beforehand, we were all ready to get our hands dirty.

One of the most interesting parts of getting involved in a dig like this is that while the directors and supervisors were well-seasoned, the site itself was essentially starting in many areas with virgin soil. Previous excavations had been carried out several decades before (in a few areas), and more recently a commissioned archaeological dig had been done by a commercial unit. But a variety of reasons, the work being done in this season could be viewed as the ground work for the future of the site. That is an exciting prospect for anyone to be a part of, but I was especially keen since my understanding of how to supervise a trench was somewhat problematic. I was fairly sure there was a lot that I did not yet understand, but was keen to get in and learn.

Coming to train on this dig, I was pretty keen to support younger students and help them feel confident. One or two items tend to come up whilst excavating in field schools which I tried to be mindful of. Traveling alone for the first time and living in a large group can push peoples comfort boundaries (shocking, I know). So with experience traveling quite a lot in Italy, and the last six months of working for Italiarail (the American vendor for the train network in Italy, Trenitalia), we were able to give advice and help sort out peoples’ logistical issues fairly easily! All these things in mind, it was a grand opportunity and beautiful location.

The Site

Aeclanum is situated in modern Mirabella Eclano, Irpinia region of Campania (inland). Connected by the legendary Roman road-building, Aeclanum was situated in a central point along the Via Appia. During the Social Wars (around 89 BCE), Aeclanum had been sacked by Sulla’s forces. It was rebuilt, and seemingly flourished in the 2nd CE when it became the Colonia Aelia Augusta Aeclanum. There is evidence of many phases of rebuilding, additions and repairs/re-purposing until Aeclanum sort of disappears from history after 662 from the campaigns against the Lombards of Benevento.

The site itself was set within some idyllic green hills and edible vegetation was scattered throughout. Quite a few buildings were excavated and reconstructed already on the site, which drew tourists to this lovely town. Some building identifications are being reviewed, as new methodologies and interpretations were being applied to this site. There were number of specialists on-site to do digital mapping, ceramic analysis, and even drone photography (which took brilliant photos)! There were many types of dwellings, buildings and some roads visible. The scope of the site is not yet fully known, but there were many intriguing possibilities.

Our group was a mix of University students from all levels and people who came on this dig to get experience for a career shift as they sought to start a new direction in their lives, which is always commendable!

The energy and efforts of the students was amazing. Rain or shine, our team of Saggio Cinque was a hard-working group, and hilarious. My senior supervisor (who I tried to learn as much as possible from) brought very approachable and engaging teaching methods to the site which was a huge help.

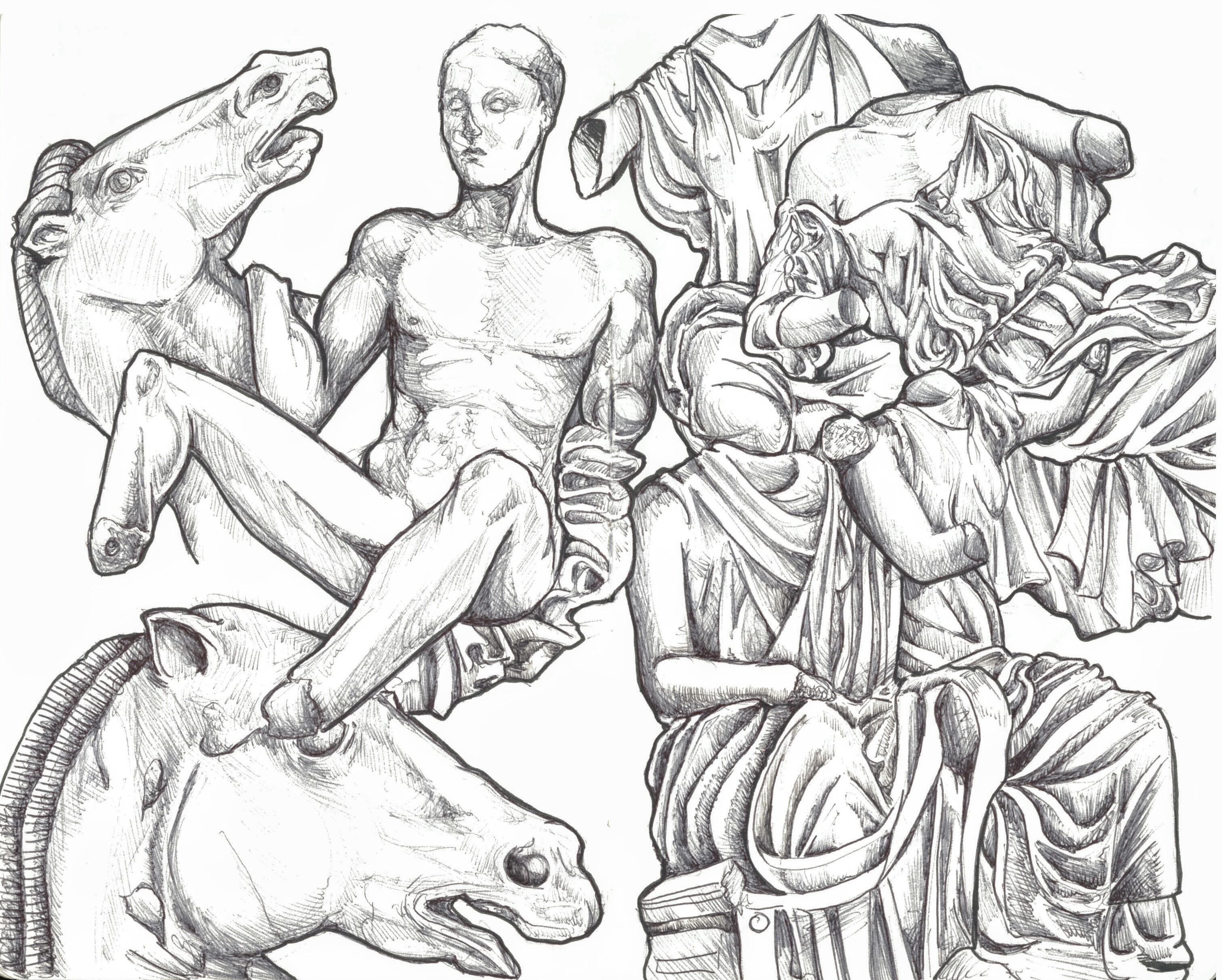

Of course! The work is so beautiful on its’ own that it seems a completed decoration. Though I cannot do the architecture justice through simple quick pen sketches in my Moleskin, I do keep trying!

All in all, these were not box-ticking learning objectives, rather an attempt at trying to give a taste of the concrete outcomes they needed to start a career in archaeology. I may have only a few weeks as a junior supervision, but it was incredibly informative right away being on the other side of a field school.I can’t go in to much detail, or perhaps shouldn’t, as it is an evolving and ongoing project and season, so what I can say about what we encountered in Saggio Cinque (now famously under the hashtag #SaggioCinque) was the following.

My previous dig experience in Greece included evidence of ancient and modern grave robbing. Working on a salvage dig was fast-paced and quite hush-hush about what we found, since the graves were near the surface and not hard to spot. Whereas, what was surprising in Aeclanum, was seeing the evidence of someone trying to remove the massive limestone slabs (unsuccessfully) and apparently giving up. Poaching finished building materials and re-purposing them for newer buildings was pretty standard practice in antiquity, but it was interesting to see evidence of a failed attempt.

Local politics and archaeology

Whilst our archaeological field school lodged in Mirabella Eclano, there was a bit of a press furor going on around us. A sign was put up near the site, “Archaeologists in the Nursery, Moms in Revolt”, publicised a local misunderstanding about our accommodations. This strange bit of press, while seeming contentious, actually gave the opportunity for some interviews on site and publicised some of the exciting things we were doing.

To hear an interview with our site directors, you can check out this Sound Cloud link: https://soundcloud.com/airadioariano/aeclanum-sta-per-concludersi-la-prima-fase-della-campagna-di-scavo

Mirabella Eclano

The town of Mirabella Eclano was full of affordable little restaurants and bars, beer festivals, and very pretty views. The people of Mirabella Eclano were always very kind and gracious. I had a lot of great conversations using a mixture of French/English/Italian with quite a few locals. There were some real gems of cafes and restaurants; my favourite cafe, Zucchero e Vaniglia, served some incredible pastries and perfect portable coffees- superior additions for a dig break. Our main port of call, however, was the cafe/bar at Hotel Aeclanum. Many drinks, chats and post-dig hangouts took place at this hotel bar.

If you are curious and would like to find out more or maybe get involved, please check out the Apolline Project Website: http://www.apollineproject.org

Ciao for now!

Situated next to the Olympeion, the Arch of Hadrian has quite a few stylistically complex elements and details which are exemplary of Athenian architecture done in a Roman-style. Created from solid Pentelic marble, Corinthian capitals atop pilasters among other features, are representative of architectural imagery in Roman wall painting. There were sculptures in the central niche, it has been suggested, which were of Hadrian and Theseus. This is not such an odd paring when you consider the inscriptions.

Situated next to the Olympeion, the Arch of Hadrian has quite a few stylistically complex elements and details which are exemplary of Athenian architecture done in a Roman-style. Created from solid Pentelic marble, Corinthian capitals atop pilasters among other features, are representative of architectural imagery in Roman wall painting. There were sculptures in the central niche, it has been suggested, which were of Hadrian and Theseus. This is not such an odd paring when you consider the inscriptions.

Hadrian’s Library

Hadrian’s Library

One of the key buildings in the Roman Agora of Athens, which continues to impress tourists on the north side of the Acropolis, is the Tower of the Winds. As with the other buildings in Athens, it was built of that familiar Pentelic marble into a twelve-meter high clock tower. The building had just been restored with the scaffolding removed before I arrived, which was excellent timing to see a very ornate and beautiful ‘horologion’, or timepiece.

One of the key buildings in the Roman Agora of Athens, which continues to impress tourists on the north side of the Acropolis, is the Tower of the Winds. As with the other buildings in Athens, it was built of that familiar Pentelic marble into a twelve-meter high clock tower. The building had just been restored with the scaffolding removed before I arrived, which was excellent timing to see a very ornate and beautiful ‘horologion’, or timepiece.

The Roman Agora shows another product of the Italic investment in the city of Athens. Marking the entrance to the west of the Agora, it bears a dedication to ‘Athena the Originator’, not unlike the other monuments in Athens. However, the Roman gifted through the generosity of Julius Caesar and his son, the Emperor Caesar Augustus.

The Roman Agora shows another product of the Italic investment in the city of Athens. Marking the entrance to the west of the Agora, it bears a dedication to ‘Athena the Originator’, not unlike the other monuments in Athens. However, the Roman gifted through the generosity of Julius Caesar and his son, the Emperor Caesar Augustus.

The Antigonid’s took over leadership of Macedon and Greece following the end of Alexander the Great’s family line, and successfully wielded the same ideology to justify their control over the Greeks: ‘protectors of Greek freedom’, an iron fist in a velvet glove so to speak; they controlled Greece through benevolent subjugation. Through the general practice of eugaritism (benefaction for honours), the Greeks were given beautiful buildings, festivals, and money in return for obeisance to Macedonian authority. For their own part, the Greeks had spent the last few hundred years restlessly under the yoke of the Macedonians, who they considered barely civilized.

The Antigonid’s took over leadership of Macedon and Greece following the end of Alexander the Great’s family line, and successfully wielded the same ideology to justify their control over the Greeks: ‘protectors of Greek freedom’, an iron fist in a velvet glove so to speak; they controlled Greece through benevolent subjugation. Through the general practice of eugaritism (benefaction for honours), the Greeks were given beautiful buildings, festivals, and money in return for obeisance to Macedonian authority. For their own part, the Greeks had spent the last few hundred years restlessly under the yoke of the Macedonians, who they considered barely civilized.

What is the Hellenistic Period?

What is the Hellenistic Period?

Considered to be the first theatre in the world, it was used to honour the god of wine, revelry and theatre, Dionysus. Prior to anyone getting on with the show, a jaunty sacrifice of a bull was needed to kick off proceedings and purify the theatre. The festival of the Dionysia was celebrated here, with some of the biggest names in Classical literature of the age: Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes and Aeschylus.

Considered to be the first theatre in the world, it was used to honour the god of wine, revelry and theatre, Dionysus. Prior to anyone getting on with the show, a jaunty sacrifice of a bull was needed to kick off proceedings and purify the theatre. The festival of the Dionysia was celebrated here, with some of the biggest names in Classical literature of the age: Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes and Aeschylus. There were several phases of the Theatre of Dionysus, commencing with wooden seating in the 6th century BCE. The theatre is currently in pretty rough shape, though reconstruction work was completed between 2009 – 2015. The main problem, as with most buildings from antiquity, was that much of the stone was pilfered and used in other buildings nearby, or possibly carried off to be burned down in lime kilns.

There were several phases of the Theatre of Dionysus, commencing with wooden seating in the 6th century BCE. The theatre is currently in pretty rough shape, though reconstruction work was completed between 2009 – 2015. The main problem, as with most buildings from antiquity, was that much of the stone was pilfered and used in other buildings nearby, or possibly carried off to be burned down in lime kilns.

Rather than making the riskier financial decision to invest in the support of new plays, which perhaps cut too closely to home (really reflecting the loss of autonomy felt by Greeks), instead the attention was focused on a golden age where their independence was trumpeted and powerful.

Rather than making the riskier financial decision to invest in the support of new plays, which perhaps cut too closely to home (really reflecting the loss of autonomy felt by Greeks), instead the attention was focused on a golden age where their independence was trumpeted and powerful. Awarded to the choregos, who was responsible for the training and sponsoring of the chorus in dramatic contests held in the Dinonysia, this is the only existing example of remaining in Athens today. Sculptures like this, would have been crowned with a bronze tripod which no longer survives. The limestone podium is topped with a cylindrical tholos of Pentelic marble, and six Corinthian columns which are topped by eight acanthus leaves.

Awarded to the choregos, who was responsible for the training and sponsoring of the chorus in dramatic contests held in the Dinonysia, this is the only existing example of remaining in Athens today. Sculptures like this, would have been crowned with a bronze tripod which no longer survives. The limestone podium is topped with a cylindrical tholos of Pentelic marble, and six Corinthian columns which are topped by eight acanthus leaves.

The story of the Erechtheion was one of constant change. Built to replace the Old Temple of Athena, though not atop its foundations, it accommodated several cults in the same space. The building’s namesake was the hero and foster-child of Athena, Erechtheus. The temple was also dedicated to Athena, Poseidon, Hephaistos, and the hero Boutes – all worshiped in the same space.

The story of the Erechtheion was one of constant change. Built to replace the Old Temple of Athena, though not atop its foundations, it accommodated several cults in the same space. The building’s namesake was the hero and foster-child of Athena, Erechtheus. The temple was also dedicated to Athena, Poseidon, Hephaistos, and the hero Boutes – all worshiped in the same space. This temple offers an interesting glimpse at what was going on in Athens as it was building an empire. Pericles and other elites of Athensbrought together a mixture of local spaces routed heavily in the foundation mythology of the city and it’s heroes, and built up expensive, impressive buildings around them.

This temple offers an interesting glimpse at what was going on in Athens as it was building an empire. Pericles and other elites of Athensbrought together a mixture of local spaces routed heavily in the foundation mythology of the city and it’s heroes, and built up expensive, impressive buildings around them. The temple is on a slope (as you can see above) which sees the west and north side three metreslower than the southeast portion of the temple.The building size was reduced as a result of the shortage in funds during the Peloponnesian War, and the Caryatids placement hid the change in design.

The temple is on a slope (as you can see above) which sees the west and north side three metreslower than the southeast portion of the temple.The building size was reduced as a result of the shortage in funds during the Peloponnesian War, and the Caryatids placement hid the change in design.

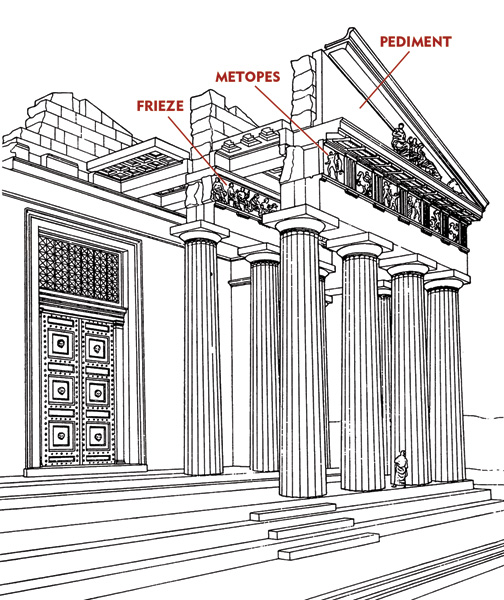

The creation of this temple dedicated to Athena began in 447 B.C.E. and lasted right up to 432 B.C.E, built atop the previous “Pre-Parthenon” also destroyed by the Persians in 480 B.C.E. Under Pericles, Phidias designed a monumental Athena statue that once stood in the Parthenon, and the sculptural motifs along the metopes and pediments and frieze, though the architectural design was Callicrates and Ictinos.

The creation of this temple dedicated to Athena began in 447 B.C.E. and lasted right up to 432 B.C.E, built atop the previous “Pre-Parthenon” also destroyed by the Persians in 480 B.C.E. Under Pericles, Phidias designed a monumental Athena statue that once stood in the Parthenon, and the sculptural motifs along the metopes and pediments and frieze, though the architectural design was Callicrates and Ictinos.

The main themes of the artist design surrounding the Parthenon focused on their history and identity. Themes of conflict are illustrated in the two sides of the metopes (almost like a film reel running along the long sides of the Parthenon). The north-facing metopes possibly depict the sack of Troy (though it is under debate).

The main themes of the artist design surrounding the Parthenon focused on their history and identity. Themes of conflict are illustrated in the two sides of the metopes (almost like a film reel running along the long sides of the Parthenon). The north-facing metopes possibly depict the sack of Troy (though it is under debate).

Did you guess that last one? Gold stars, whole class.

Did you guess that last one? Gold stars, whole class.

Future blog posts will look at some of the artistic elements of Greek art, of which the Parthenon provides excellent examples.There is a lively academic debate about the nature and meaning of the images depicted on the frieze, which Mary Beard discusses in her book “Parthenon”.

Future blog posts will look at some of the artistic elements of Greek art, of which the Parthenon provides excellent examples.There is a lively academic debate about the nature and meaning of the images depicted on the frieze, which Mary Beard discusses in her book “Parthenon”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.